Shoulder Surgery: A Path to Liberation?

This essay appeared in Chaleur Magazine, May 1, 2018 (chaleurmagazine.com)

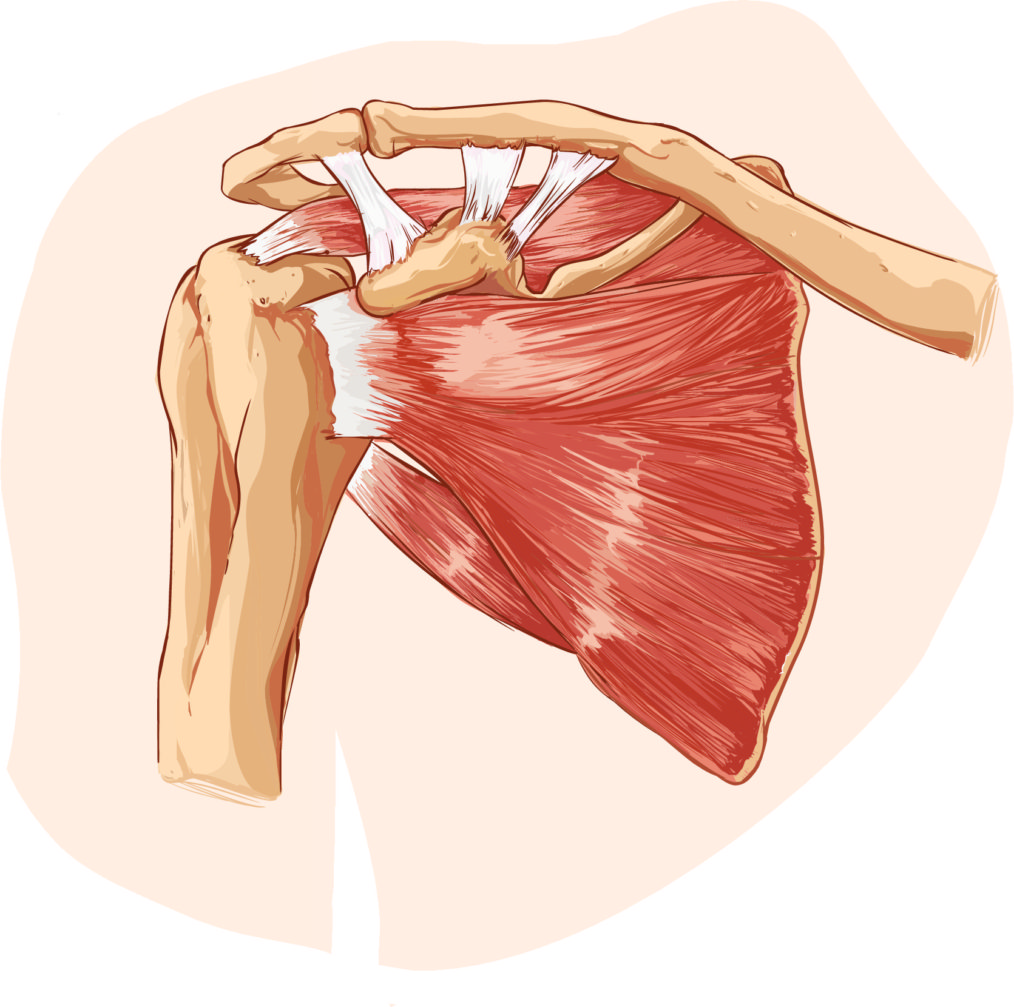

I recently underwent shoulder surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff. While the surgery is routine—repairing damaged tendons—the recovery time is not. I’m told I must be prepared to suspend life as I know it for at least six months! During this time, I must keep my arm in a sling, which means no cello, no tennis, jogging, or yoga, no driving or lifting anything heavier than a coffee cup. That’s the short list. So what’s left?

Well, some things appear not to incur the wrath of the gods. I can read the 1,000-page doorstoppers I’ve been setting aside for years, as long as I don’t lift them with my left hand. I can visit friends, listen to music, and garden with one hand.

One night, when I was tiring of War and Peace, I began looking through some research papers I had written many years ago for my graduate degree in Sanskrit. They brought memories of the endless years I spent in the deep recesses of Harvard’s Widener Library struggling with ancient texts and writing an excruciatingly long Ph.D. dissertation. As I rifled through the box, one paper caught my eye: The Diksha Consecration: Entrance to a Godly World.

The consecration is an ancient Indian ceremony, almost 3,000 years old: a rite of passage that was performed for patrons of the Soma sacrifice, an important Vedic ritual. The person being consecrated (the dikshita) is “reborn” and takes a metaphorical passage to the realm of the gods.

The dikshita must endure various challenges that to a Western sensibility may seem bizarre. For instance, he is dressed in a linen garment representing a caul, which is covered with an antelope skin, symbolizing the placenta. He scratches himself with an antelope horn, lest he injure his tender (embryonic) skin. Bodily hair is shaven, and his nails are cut. He is scrubbed down and anointed, wears a girdle, and sits with clenched fists near a fire in a hut whose beams run in the direction of the gods. In this purified state, he sits near a scorching fire from midday to dusk accumulating inner psychic heat (Sanskrit tapas) and is forced to remain particularly alert, lest his psychic energy be dissipated. The heat “burns” him in an act symbolic of death. Then he is turned into an embryo, ready for rebirth. Later, he must creep across an antelope skin on his metaphorical journey to heaven.

Reading the paper after so many years, I was struck by how similar these activities seemed to my current predicament. Before surgery, I had to fast; in the hospital, I was scrubbed down, the hair on my arm was shaved, and now I’m wearing a large, bulky, black sling—a kind of girdle—although it feels more like I’m carrying an AK-47.

Moreover, the person being consecrated is made to do everything in reverse from what he would do normally. He uses the opposite hand to eat, his nails are cut starting from his right hand (when they normally would be cut starting from the left), and any hair that was left uncut is combed on the opposite side from normal practice.

Like a dikshita, I am using the “wrong” hand to eat (my right, since I’m a lefty); I put my left arm through my shirtsleeve before the right, the opposite of my daily routine; and I’m forced to sleep on my back or my “wrong” (right) side. While I haven’t taken to scratching myself with an antelope horn, I’ve had to find creative ways to reach itchy bodily parts no longer accessible with my left hand. My wife ties my shoes. Although I’m not sitting by a fire to generate internal psychic heat, I numb my shoulder three times a day with a $150 “cold-rush therapy system” from Amazon. In effect, my world feels oddly like that of the dikshita—upside down and inside out.

The “reverse” actions of the ancient rite are supposed to help the one being consecrated to emerge as a newborn—awkward and disoriented. In this way, he is readied to enter a higher plane, one free of the passions, whether dark or light, of the earthly life.

I don’t claim to have ascended to the realm of the gods. Nevertheless, I’ve noticed a strange thing: despite moments of frustration, I suddenly realize a silver lining in turning one’s daily routine off autopilot mode: I have become more mindful—recall the dikshita’s need to be alert—and appreciative of the everyday activities that make up my waking hours. Being confined to one hand has a way of focusing the mind. When I’m eating, I’m eating; when I’m making coffee, I’m making coffee; when I’m walking down a slippery slope, I’m walking down a slippery slope. I try hard to accept my situation without judgment. So, while I’m no dikshita, I feel that my surgery and healing process have brought me one step closer to a mental state that is both joyful and liberating—a rebirth, of sorts.